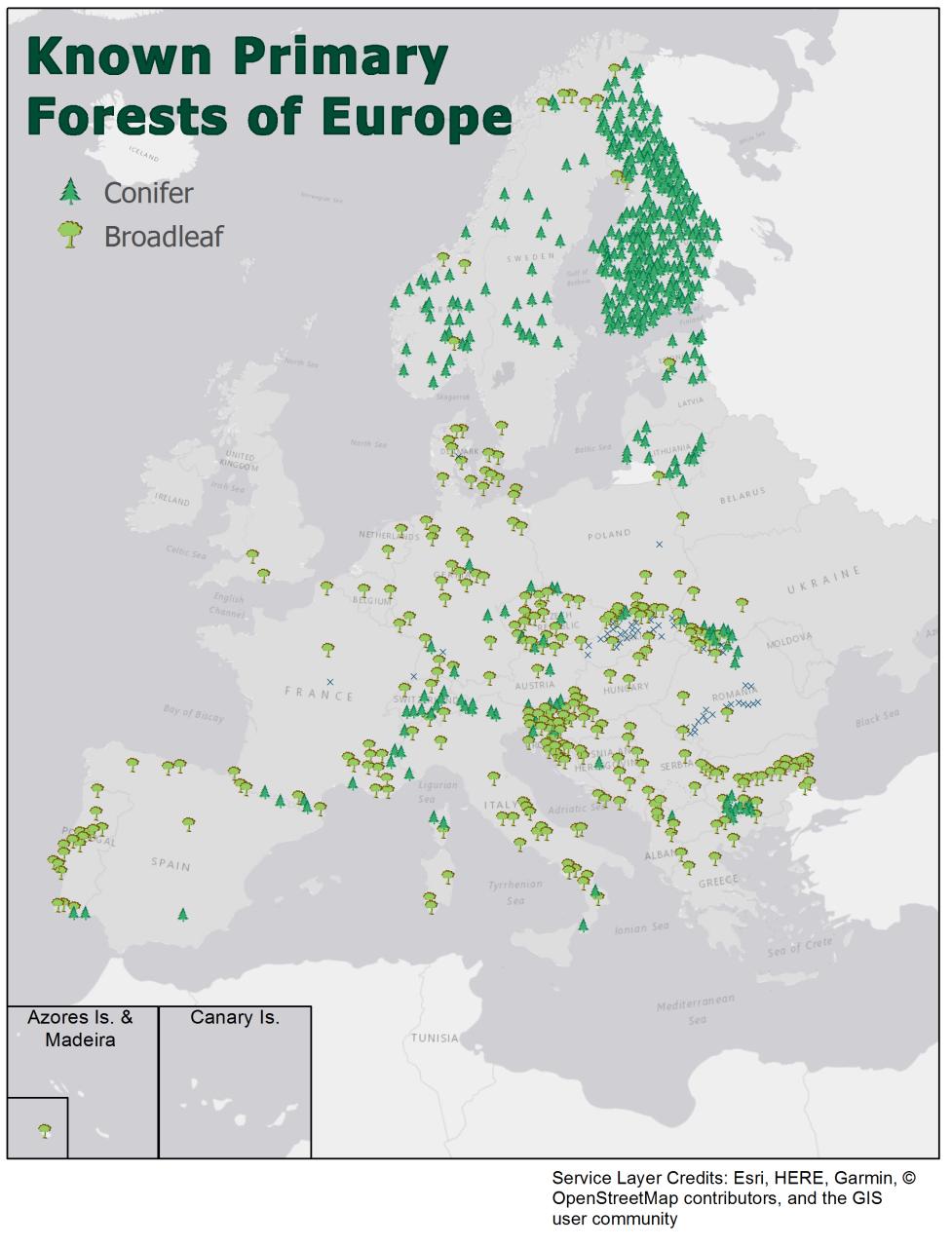

Though you might read about deep, dark woods in fairy tales, the prevailing story today is that very little European old-growth forest remains. But now a new study—and map—shows that a surprising number of these primary forests still stand.

“What we’ve shown in this study is that, even though the total area of forest is not large in Europe, there are considerably more of these virgin or primary forests left than previously thought—and they are widely distributed throughout many parts of Europe,” says Bill Keeton, a forest ecologist at the University of Vermont. “And where they occur, they provide exceptionally unique ecological values and habitat for biodiversity.”

Keeton was part of a team—led by researchers from Humboldt University in Berlin, Germany—who created the first map of Europe’s last wild forests. The map identifies more than 3.4 million acres in 34 European countries—and was published in the journal Diversity & Distributions on May 24, 2018.

Precious patches

“It is not that these forests were never touched by man. This would be hard to believe in Europe,” explains Humboldt University scientist Francesco Maria Sabatini, lead author of the study. “Still, these are forests where there are no clearly visible indications of human activities. Maybe that’s because they were blurred by decades of non-intervention, where ecological processes follow a natural dynamic.”

The compilation of the map was a huge task. “We contacted hundreds of forest scientists, experts, and NGO activists from all over Europe asking to share information on where to find such forests in their country,” says Sabatini, a post-doctoral researcher at Humboldt. “Without their direct engagement, we could have never been able to build our database, which is the most comprehensive ever compiled for Europe.”

The study highlights that primary forests in Europe are generally very rare, located in remote areas, and fragmented into small patches. “The European landscape is the result of millennia of human activities, so it is not surprising that only a small fraction of our forests are still substantially undisturbed,” explains Tobias Kuemmerle, director of the Conservation Biogeography Lab at Humbolt University and the senior author on the study. “Although such forests only correspond to a tiny fraction of the total forest area in Europe,” he says, “they are absolutely outstanding in terms of their ecological and conservation value.”

Primary forests are often the only remaining harbor for many endangered species, Kuemmerle says, and scientists consider them as natural laboratories for understanding people’s impact on forest ecosystems. “Knowing where these rare forests are is therefore extremely important,” he says, “but, until this study, no unified map existed for Europe.”

Cutting continues

“Europe has really been at the forefront of establishing continent-wide protected areas networks,” says UVM’s Bill Keeton, who has studied forests in Europe for more than a decade and chairs a working group on old-growth forests for the International Union of Forest Research Organizations. But the new study also shows that the preservation of these remaining fragments of primary forest cannot be taken for granted, not even in Europe. The majority of these forests are small and interspersed in human-dominated landscapes, which makes them particularly prone to human disturbance.

The new study reports that most—89 percent—of the primary forest mapped is in protected areas, but only 46 percent of this land is under strict protection. This means that, at least in some European countries, timber harvesting or salvage logging may jeopardize the wild nature of these forests.

“Wide patches of primary forest are being currently logged in many mountain areas, for instance in Romania and Slovakia and in some Balkan countries,” says Miroslav Svoboda, a scientist at the University of Life Science in Prague and a co-author of the study. “A soaring demand for bioenergy coupled with high rates of illegal logging, are leading to the destruction of this irreplaceable natural heritage, often without even understanding that the forest being cut is primary.”

It’s an irony, Svoboda says, that in many cases logging is done legally, even within national parks. “Primary forests have an exceptional value, both environmental and cultural,” he says, “and preserving their integrity should be a priority of any EU environmental strategies.”

Map to protect and restore

The scientists are confident the new map can help protect Europe’s remaining old-growth forests. “We clearly demonstrated that the distribution of remaining primary forest is the result of centuries of land use and forest management,” said Sabatini. In his view, understanding the human-caused pressures behind the current distribution of primary forests can inform future protection and restoration efforts.

“We used the new map to calibrate a model highlighting areas where land-use pressure is low,” says Sabatini, “to predict where other patches of primary forest, not yet mapped, are likely to occur.” Even if these areas turn out to not hold primary forest, he says, they still may be good places for forest restoration initiatives at relatively low cost.

In other words, the new research may point toward “hundreds of additional sites that are worthy of consideration for possible protection,” say Bill Keeton, a professor of forestry and forest ecology in UVM’s Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources and a fellow in UVM’s Gund Institute for Environment. “We may find areas that are good to include in an expanded World Heritage Network or given other conservation status.”